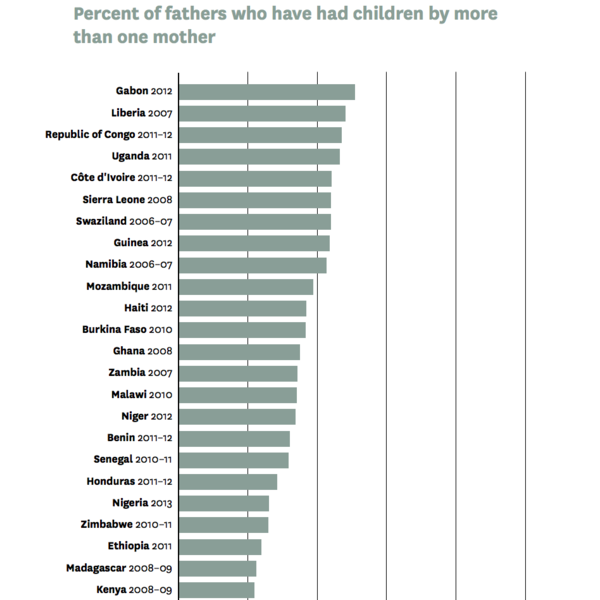

AFRICAN men particularly Ugandan men are among the most likely in the world to father children with more than one woman, a new report indicates.

Out of 39 countries around the world, African countries take up 25 slots on the rankings where men have children with multiple women, theState of The World’s Fathers report reveals.

The multi-women fathers include polygamous men, married men who cheat on their partners, and unmarried men having sexual relationships with different women.

Gabon, Liberia, Republic of Congo and Uganda are the top countries where the highest percentage of men having a child with more than one woman, at more than 45% of adult men, data from demographic and housing surveys shows.

The report was published by MenCare; a global campaign to promote men’s involvement in parenting and caregiving.

Although the data doesn’t show whether the multiple relationships are simultaneous or sequential, the report indicates that having children with more than one partner “complicates decisions to plan, prevent, or time a pregnancy.”

The report explores the changing and, sometimes, fraught role of fathers as caregivers, which has been nearly invisible in public discourse – instructively, this is the first time a global status report on fatherhood has been published, while the State of the World’s Mothers has been published since 1999 and State of the World’s Children has been published since 1996.

Men are often stereotyped as “clueless” when it comes to raising children, with both men and women believing that women are more “naturally” wired to be caregivers – attitudes which are tied to essentialist beliefs about the nature of men and women.

In fact, both fathers and mothers, as well as policymakers and the wider society harbour “deep-seated suspicions of men’s capabilities as intimate caregivers. These translate into reluctance to offer support,” the report states.

But new research shows that men are as deeply wired for emotional connections as women are, and the supposed “natural” caregiving that women espouse are much more as a result of socialisation.

The research shows that men’s bodies respond with comparable hormonal shifts in response to physical contact with children; when men hold babies, their oxytocin and prolactin hormone levels – the “bonding hormones” – increase.

These are analogous to the hormones released by mothers when breastfeeding, that primes both men and women to ignore distractions and channel all their attention to the needs of the young child.

The conclusion emerging from this research that although its taken for granted that women have an innate ability to care for children, men have an equivalent or, at the very least, similar proclivity to care for children, just as women can do things that historically have been deemed a father’s role, such as playing sports with their children and providing financially for the family.

Men’s involvement in care giving is increasing in some parts of the world, but nowhere does it equal that of women. Women now make up 40% of the global formal workforce, yet they also continue to perform two to 10 times more care giving and domestic work than men do.

Most African countries have some form of official paternity leave, though in 29 countries in Africa, it is just 1-6 days. Tunisia gives one day paternity leave, South Africa and Tanzania give three days, Ethiopia gives five days of unpaid leave “in the event of exceptional or serious events.” Kenya is one of Africa’s most generous, mandating two weeks of paid paternity leave.

Although men might want to be more involved in raising children and in domestic tasks, there is often a lot of resistance and stigma – especially from the very women they want to help. Many women view the home as the one sphere where they are in control, and so resist what they perceive as a man’s infringement on their domain.

According to one study (though the country is not specified), women and their mothers-in-law worried that if men became more involved in the home, the community would view the husbands as “enslaved” or “bewitched” by their wives.

Research with Rwandan men who participated in fathers’ groups found that despite men’s interest in caregiving, they were hesitant to take on tasks that ran counter to “everything they were taught a man should do.” The men even acknowledged that they often hid their participation in household chores from other men and the wider society.

The report also indicates that although single motherhood is on the rise, as economic and social shifts leave many men unmoored. In South Africa, for example, 52% of children under the age of 15 live in mother-headed households.

Still, despite the ‘deadbeat’ stereotype, data from South Africa shows fathers are often closely involved in their children’s lives, whether they are resident in the home or not; half of non-resident fathers report seeing their children several times a month or more often.

Although living with both biological parents in a happy, healthy home is the ideal scenario for children to grow up in, real life is messier, but all is not lost.

“Children thrive in all types of families,” the report says, “but the most important protective factor for child well-being is having multiple, supportive caregivers, regardless of their sex.”

There’s much hand wringing in Africa about whether fathers serve as good “male role models”, particularly for their sons. But there’s an increasing recognition that the most important outcome for raising healthy, well-adjusted children is how a caregiver interacts with a child, and not the explicit transmission of gendered roles.

Addressing fathers, the report states, “Your child needs you as a caregiver, not because of what you can contribute as a man, but because of what you can contribute as a caring human being.”

Michael Lamb, a noted fatherhood researcher, says of fathers’ impact on children: “The characteristics of the father as a parent rather than the characteristics of the father as a male adult appear to be most significant [in successful raising of children].”

Article By Swali Africa